Sunday, October 23, 2011

Mansfield Park

I can’t say it was as exciting as the last two Austen novels I read (Emma and Northanger Abbey) but it appeared to be A LOT more interesting while I was reading due to it following so close to putting down Samuel Richardson’s Pamela. After Richardson’s work it was like watching one of the Die Hard films after watching a documentary about the process of making paint (as you know I didn’t hate Pamela I just found it to be a real exercise in patience).

The reason I bring up Richardson’s epistolary novel is due to Fanny Price being a very similar character to Pamela Andrews (low status girl educated in a household of a much higher class; pursued by an unwanted, and then at least slightly admired, lover; and, a serious sense of duty and virtue). However, there is one HUGE difference, Fanny is a much more believable character (at least to this modern reader). Fanny does not deny any intrigue she has regarding things that lie on the line of her morals but still puts her duty to the Bertrams and virtue before her own desire (unlike Pamela who just denies that cravings of this sort exists at all).

Fanny isn’t the only loveable character in this novel filled with some rather scandalous characters (wink wink, nudge nudge- Henry Crawford with both the Bertram sisters). Fanny’s cousin and future husband (don’t worry it is okay back in the early 1800s), Edmund Bertram is a very positive individual and would have been a perfect role model for young male readers at the novel’s release. Although he can be rather naive at times, he is constantly the lighthouse of support for Fanny and always treats her as an equal. Equally as supportive to Fanny is her Uncle, Sir Thomas. Although it is indicated that Fanny did not always find love from him, he begins to see her worth as an individual after he returns from Antigua. Although her Aunt, Mrs. Norris, would love to see Fanny treated in the manner her lower station could provoke, Sir Thomas takes it onto himself to give Fanny the same opportunities he gives his own daughters, Maria and Julia.

In romantic nature, Fanny is rewarded for her patience and virtue in life and gets the man of her dreams- Edmund. Although Austen tackles a narrative based around the clash between morals and desires it never becomes ‘preachy’ and is constantly an enjoyable read that had me rooting for Fanny throughout.

The edition I read was ISBN: 0-14-062066-4.

Citation:

Austen, Jane. Mansfield Park. Toronto: Penguin, 1994. Print.

Saturday, October 22, 2011

Titus Andronicus

Among other things, the play focuses around the conflict between the Andronicus family and Tamora’s Goth family; for this reason, children (although not necessarily youth) fill the scenes. However, not all the children present indicate a change in views that will bring about the positive future discussed above, the individuals that do include; Bassianus, Lucius, and young Lucuis. For the purpose of my argument, please note that Bassianus is deemed a ‘youth’ or ‘child’ due to him being younger than his brother Saturninus.

After the death of the Roman Emperor, Saturninus fights to become emperor. He does this not because he would be the better ruler for Rome but because he believes in the pre-established monarchy and his right to the throne as the eldest son. When he supposes that Titus is not going to support him he instantly shouts “Patricians, draw your swords, and sheathe them not/ Till Saturninus be Rome’s emperor” (I.i.208-9). On the other hand, Bassianus fights for a more democratic government and respects whatever decision will be made, as the best thing for Rome, confirming this with Titus by saying ““Andronicus, I do not flatter thee,/ But honor thee, and will do till I die” (I.i.215-6). As can be seen in the language, Saturninus is an instantly angry, unreasonably and self-interested person, whereas the younger Bassianus supports whatever is for the greater good of Rome’s inhabitants. Through Bassianus, Shakespeare is showing a more reasonable thought process held by the younger characters.

Although a warrior like his father, Lucius Andronicus holds a more modern idea of honour and would sooner protect his family than any promises to the city-state. After his brother, Mutius, has been killed trying to protect Lavinia, Lucius instantly stands up to his father, “My lord, you are unjust, and more than so,/ In wrongful quarrel you have slain your son” (I.i.295-6). Lucius is not only willing to protect his family but also put himself in harm’s way to do so; at the time, Rome held a view of power being given to elders yet Lucius sees that the only way to truly be a family man he must stand against his elder, Titus. It is hard to argue that protecting ones family is a complete sign of unselfish values but it isn’t just his own kin that Lucius tries to keep safe. When Aaron the Moor reveals that he has a baby and asks Lucius “To save [his] boy, to nourish and bring him up” (V.i.84), Lucius doesn’t falter in replying “Even by my god I swear to thee I will” (V.i.86). Although Aaron the Moor was integral to; the rape and dismemberment of Lavinia, the death of Quintus and Martius, and the amputation of Titus’s hand, Lucius does not hold a grudge against the blameless baby but protects it due to it’s innocence. In addition to the hatred he holds for Aaron, the baby is also half negro, and although that would give the child less rights at the time, Lucius can still “say thy child shall live” (V.i.69). In protecting Aaron’s child, Lucius shows a shift from feudal blood grudges and moves into a more educated way of thinking by understanding that individuals shouldn’t be held responsible for the crimes of their family; which is the complete opposite of his way of thinking at the beginning of the play when he demands,

the proudest prisoner of the Goths,

That we may hew his limbs and on a pile

Ad manes fratrum sacrifice his flesh

Before this earthy prison of their bones.

(I.i.99-102)

Even during the narrative of the play we can see the maturing of Lucius’s understanding of the world; this provokes the audience into believing only good can from Lucius after the curtains close.

Lucius’s good deeds are also extended to his enemies, he will do what is right even for those that have wronged him and his family. When Saturninus dies, Lucius still orders “some loving friends convey the emperor hence,/ And give him burial in his father’s grave” (V.iii.191-2). Even though he has just murdered Titus, Lucius still provides a respectful burial for the former emperor as it is the honourable thing to do despite their former differences. This is completely opposite to the way we could imagine Titus would have acted in the same situation, especially considering when Lucius pleads to “let us give him burial” (I.i.350), regarding his slain brother Mutius, Titus replies,

Traitors, away! He rests not in this tomb:

This monument five hundred years hath stood,

Which I have sumptuously re-edified.

Here none but soldiers and Rome’s servitors

Repose in fame; none basely slain in brawls.

Bury him where you can, he comes not here.

(I.i.352-57)

Titus wouldn’t even allow his own son to get a admirable burial due to a family disagreement but Lucius can put aside differences with an enemy to do the right thing. Through the father and son, Shakespeare is showing us a shift from unreasonable, fiery actions to more logical, moral decisions.

These positive changes in Lucius are also passed on to his son, Young Lucius. When Titus is wrapped up in terrible events that have fallen on his daughter, Young Lucius suggests “Good grandsire, leave these bitter deep laments./ Make my aunt merry with some pleasing tale” (III.ii.46-7). The Grandson is able to understand that Titus focusing on his own pain is not beneficial to helping the situation that has and his energy would be better put towards actually helping his daughter deal with her own pain.

In Titus Andronicus, Shakespeare contrasts the actions of the youth with those of the elders to show that the future of Rome is likely to take a positive turn and move from barbaric actions to a civilized way of solving problems. The words and actions of these figures of youth throughout the play symbolize this change when compared to the pre-established ideals of Rome we can see in the older characters.

The edition I read was ISBN: 978-0-14-071491-3.

Citation:

Shakespeare, William. Titus Andronicus. Toronto: Penguin Pelican Shakespeare, 2000. Print.

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

Tess of the d'Urbervilles

Each of the trials and tribulations that Tess Durbeyfield/ d’Urberville faces can be traced back to her father receiving this news- epiphany- in the first chapter of the novel. As David Lodge states in his The Art of Fiction, “An epiphany is, literally, a showing” (146); this ‘showing’ is not guaranteed to bring about positive or negative results but will inevitably bring about a change of some kind. Although Sir John believes this new found kinship will bring his family close to a state of nobility, as his wife puts it “great things may come o’t” (59), it is the Parson’s news that instigates all of the actions that eventually lead to Tess’s fall.

From the moment the Durbeyfield family receives their epiphany Tess’s collapse has seemingly been set in fate, “as Tess’s own people down in those retreats are never tired of saying among each other in their fatalistic way: ‘It was to be.’ There lay the pity of it” (Hardy 119). All of the choices made by Tess, or for Tess, stem from her newfound heritage and would not have come about without this initial news. This relies heavily on an established past existing before the novel even begins; if the Parson had kept his resolution “not to disturb [Jack] with such a useless piece of information” (Hardy 44) then we could assume that Tess’s life in Marlott would have continued as she expected (a simple, peaceful and safe life like that of her Mother and Father); Hardy shows this when he describes Tess’s state of mind when she does leave to ‘claim kin’ with Mrs. d’Urberville, “she had hoped to be a teacher at the school, but the fates seemed to decide otherwise” (88). Hardy confirms in this language that there were certain expectations Tess had for her life that are disrupted only by the epiphany introduced at the beginning of the text. This is expressed again later in the text, after the death of Sorrow, when Hardy explains that “before going to the d’Urbervilles’ [Tess] had vigorously moved under the guidance of sundry gnomic texts and phrases known to her and to the world in general, no doubt she would never have been imposed on” (149). In this selection it is confirmed that if the epiphany had not intervened Tess would have likely lead a happier, more traditional life and would have never been ‘imposed’ upon and thrust into the events leading to the unraveling of her pure life.

As already seen in the selections of quotes above, Thomas Hardy uses his language consistently to ground Tess’s future in fate. In the nature of fate, it is not strictly the news the Parson delivers that causes the epiphany but whom he delivers it to; as David Lodge explains the epiphany comes when “reality is charged with a kind of transcendental significance for the perceiver” (147). The epiphany is triggered by the importance Sir John puts on the news not by the news itself. This interaction between Parson Tringham and Jack Durbeyfield as the cause of Tess’s ruin is expressed by Angel Clare who, after receiving news of Tess’s sordid past, exclaims that he “think[s] that parson who unearthed [Tess’s] pedigree would have done better if he had held his tongue” (302). Although Angel does not necessary use the language of epiphany, he is putting the weight on this revelation as the sole cause of the tear between himself and Tess in what seemed to hold the potential for a perfect marriage and a blissful future.

Even after the death of her husband, Joan Durbeyfield’s choices are propelled by her husband’s emphasis on the d’Urberville heritage. This is what leads Tess and her family to set their sights on Kingsbere and, in turn, into the hands of Alec d’Urberville. As Tess explains, after Alec asks where they will be going, “Kingsbere. We have taken rooms there. Mother is so foolish about father’s people that she will go there” (Hardy 438). Joan does not take the time to chose a place most suitable for her remaining family to settle but uses the information provided by the Parson as the only determining factor leading her to a place that will lead to their homelessness. Although she can see that this is foolish, Tess is yet again caught up in the knock on effects of the epiphany.

When an epiphany occurs it is not possible to state whether the effects will be positive or negative; to Tess the consequence of the initial epiphany is considerably destructive. However, the exact same epiphany will, presumably, lead to a decent future for another character, Liza-Lu. When Tess predicts her final demise she asks Angel to “marry [Liza-Lu] if you lose me” because “she has all the best of me without the bad of me” (Hardy 485). Through this request, Hardy is showing us that if Tess had escaped the consequences of the epiphany she would have escaped all the ‘bad’. Although Tess loses her virtue, her husband, and her life, the same cause of this loss is what will lead to Liza-Lu likely living a good life with Angel Clare; the novel ends with that Western sign of affection as the two characters “[join] hands again, and [go] on” (Hardy 490).

In Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Thomas Hardy delves into the potential destruction possible with the modern epiphany. Hardy places this epiphany at the very beginning of his novel so he has the full narrative to investigate just how a life can be changed- shattered- with a single discovery.

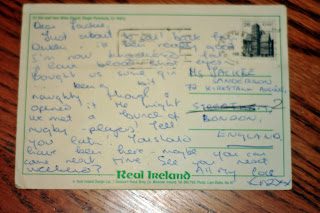

Additionally, the second-hand copy of Tess that I picked up came with another unusual bookmark (remember the old CN ticket holder that I got with Thomas Mann's Death in Venice, Tristan, and Tonio Kröger) a lovely postcard.

It is likely you can't read what is on the back so here it is; "Dear Jackie,

Just about to sail back from Dublin, it's been really good. I'm now knackered, fat, I have blood shot eyes. Bought us some gin... been a bit naughty though and opened it the night we met a bunch of rugby players! Tell you later! You should have been there- maybe come next time. See you next weekend?

All my love

Kaz xx"

We can only guess what Kaz was up to with those gin-chugging rugby players!

The edition I read was ISBN: 0-14-043-135-7.

Citation:

Hardy, Thomas. Tess of the d'Urbervilles. Markham: Penguin Books, 1983. Print.

Lodge, David. The Art of Fiction. Toronto: Penguin Books, 1992. Print.

Monday, October 3, 2011

The Trial

Kafka manages to make you feel just as lost as Josef K., the main character, in the events that make up the year of The Trial. When K. is confused, you are confused. When K. questions the ‘facts’ provided to him around the mysterious laws, you question those facts. When K. considers just giving up, you consider just putting down the book because you can’t make sense of it (although you won’t because you really want to see how it all ends).

I am arguably very judgmental of fictional characters and either root for, or against, them continually throughout the course of a narrative. However, I found myself constantly torn between deeming K. the victim or viewing him as an arrogant arse!

As I mentioned in the start of this post, the novella will continually make you question exactly what you are reading and how it makes any sense in the realistic world the narrative inhabits. At some points, Kafka tricks you into believing the story is taking a more logical turn; however, he will suddenly throw a spanner in the work. For example, at the end of Chapter Four the narrative seems to become a more ‘regular’ story but Chapter Five immediately adds that crazy aspect the rest of the story requires;

“…he heard a sigh from behind a door which he had himself never opened but which he had always thought just led into a junk room. He stood in amazement and listened again to establish whether he might not be mistaken […] in the cupboard-like room itself stood three men, crouching under the low ceiling […] one of the men was clearly in charge, and attracted attention by being dressed in a king of dark leather costume which left his neck and chest and his arms exposed.” (Kafka 60)

K. then sees that this leather bound gentleman is beating (spanking) the two cops that arrested K. in the first chapter; this thrashing then continues for a few days.

I’m not sure about anyone else but whenever I opened junk room doors at my old office I never saw, or expected to see, a man spanking two other large men.

The edition I read was ISBN: 978-0-486-47061-0.

Citation:

Kafka, Franz. The Trial. Trans. David Wyllie. New York: Dover Publications, 2009. Print.

Saturday, October 1, 2011

The Little Foxes

The story centers around the most loathsome fictional family I have ever come across; the Hubbards. They are a southern American family living in the late 1800s/ early 1900s (the play itself is set in the Spring of 1900). They are the embodiment of all the terrible traits you would imagine linked to the rising middle class of this time that felt it their right to build themselves up in society no matter who they walked over; selfish, angry, rude, and disrespectful describes the majority of this family in a nutshell.

To be fair, this was heightened by the fact that I was reading a production version of the text; meaning that it was filled with very lengthy stage directions and not in the enjoyable novel-esque descriptions of the likes of Bernard Shaw.

The only escape from all of this came in the form of five characters;

- Addie and Cal- The servants/ slaves of Regina Giddens (an original Hubbard) who show more humanity than their, supposedly, civilized masters throughout the play.

- Birdie Hubbard- The wife of Oscar Hubbard who has a kind flame in her spirit that is slowly being extinguished by the awful Hubbard family.

- Alexandra Giddens- The daughter of Regina and Horace Giddens who, like Birdie, does not share the terrible characteristics with the majority of the family and actually seems to be the anti-thesis of her own mother.

- Horace Giddens- As stated above, the husband of Regina and father of Alexandra. He is mentioned throughout Act One but then only comes onto the stage in the final two acts and really gives the Hubbards what they deserve!

The final escape, at least for myself, was singing snatches of Malvina Reynold’s Little Boxes in my head;

Citation:

Hellman, Lillian. The Little Foxes. New York: Dramatists Play Service, Inc, 1969. Print.