The modern epiphany, as solidified by James Joyce, tended to penetrate the narrative in the latter half of the short story, novella, or novel. However, Thomas Hardy chose to present his epiphany in the first few pages of his novel Tess of the d’Urbervilles (496 pages). All the events that occur throughout the story are thus the effects of the epiphany Jack Durbeyfield receives, from the Parson, stating his family to be descendants of the d’Urberville lineage.

Each of the trials and tribulations that Tess Durbeyfield/ d’Urberville faces can be traced back to her father receiving this news- epiphany- in the first chapter of the novel. As David Lodge states in his The Art of Fiction, “An epiphany is, literally, a showing” (146); this ‘showing’ is not guaranteed to bring about positive or negative results but will inevitably bring about a change of some kind. Although Sir John believes this new found kinship will bring his family close to a state of nobility, as his wife puts it “great things may come o’t” (59), it is the Parson’s news that instigates all of the actions that eventually lead to Tess’s fall.

From the moment the Durbeyfield family receives their epiphany Tess’s collapse has seemingly been set in fate, “as Tess’s own people down in those retreats are never tired of saying among each other in their fatalistic way: ‘It was to be.’ There lay the pity of it” (Hardy 119). All of the choices made by Tess, or for Tess, stem from her newfound heritage and would not have come about without this initial news. This relies heavily on an established past existing before the novel even begins; if the Parson had kept his resolution “not to disturb [Jack] with such a useless piece of information” (Hardy 44) then we could assume that Tess’s life in Marlott would have continued as she expected (a simple, peaceful and safe life like that of her Mother and Father); Hardy shows this when he describes Tess’s state of mind when she does leave to ‘claim kin’ with Mrs. d’Urberville, “she had hoped to be a teacher at the school, but the fates seemed to decide otherwise” (88). Hardy confirms in this language that there were certain expectations Tess had for her life that are disrupted only by the epiphany introduced at the beginning of the text. This is expressed again later in the text, after the death of Sorrow, when Hardy explains that “before going to the d’Urbervilles’ [Tess] had vigorously moved under the guidance of sundry gnomic texts and phrases known to her and to the world in general, no doubt she would never have been imposed on” (149). In this selection it is confirmed that if the epiphany had not intervened Tess would have likely lead a happier, more traditional life and would have never been ‘imposed’ upon and thrust into the events leading to the unraveling of her pure life.

As already seen in the selections of quotes above, Thomas Hardy uses his language consistently to ground Tess’s future in fate. In the nature of fate, it is not strictly the news the Parson delivers that causes the epiphany but whom he delivers it to; as David Lodge explains the epiphany comes when “reality is charged with a kind of transcendental significance for the perceiver” (147). The epiphany is triggered by the importance Sir John puts on the news not by the news itself. This interaction between Parson Tringham and Jack Durbeyfield as the cause of Tess’s ruin is expressed by Angel Clare who, after receiving news of Tess’s sordid past, exclaims that he “think[s] that parson who unearthed [Tess’s] pedigree would have done better if he had held his tongue” (302). Although Angel does not necessary use the language of epiphany, he is putting the weight on this revelation as the sole cause of the tear between himself and Tess in what seemed to hold the potential for a perfect marriage and a blissful future.

Even after the death of her husband, Joan Durbeyfield’s choices are propelled by her husband’s emphasis on the d’Urberville heritage. This is what leads Tess and her family to set their sights on Kingsbere and, in turn, into the hands of Alec d’Urberville. As Tess explains, after Alec asks where they will be going, “Kingsbere. We have taken rooms there. Mother is so foolish about father’s people that she will go there” (Hardy 438). Joan does not take the time to chose a place most suitable for her remaining family to settle but uses the information provided by the Parson as the only determining factor leading her to a place that will lead to their homelessness. Although she can see that this is foolish, Tess is yet again caught up in the knock on effects of the epiphany.

When an epiphany occurs it is not possible to state whether the effects will be positive or negative; to Tess the consequence of the initial epiphany is considerably destructive. However, the exact same epiphany will, presumably, lead to a decent future for another character, Liza-Lu. When Tess predicts her final demise she asks Angel to “marry [Liza-Lu] if you lose me” because “she has all the best of me without the bad of me” (Hardy 485). Through this request, Hardy is showing us that if Tess had escaped the consequences of the epiphany she would have escaped all the ‘bad’. Although Tess loses her virtue, her husband, and her life, the same cause of this loss is what will lead to Liza-Lu likely living a good life with Angel Clare; the novel ends with that Western sign of affection as the two characters “[join] hands again, and [go] on” (Hardy 490).

In Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Thomas Hardy delves into the potential destruction possible with the modern epiphany. Hardy places this epiphany at the very beginning of his novel so he has the full narrative to investigate just how a life can be changed- shattered- with a single discovery.

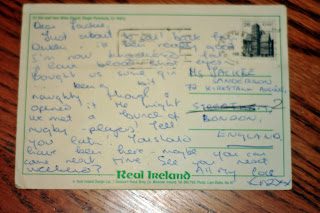

Additionally, the second-hand copy of Tess that I picked up came with another unusual bookmark (remember the old CN ticket holder that I got with Thomas Mann's Death in Venice, Tristan, and Tonio Kröger) a lovely postcard.

It is likely you can't read what is on the back so here it is; "Dear Jackie,

Just about to sail back from Dublin, it's been really good. I'm now knackered, fat, I have blood shot eyes. Bought us some gin... been a bit naughty though and opened it the night we met a bunch of rugby players! Tell you later! You should have been there- maybe come next time. See you next weekend?

All my love

Kaz xx"

We can only guess what Kaz was up to with those gin-chugging rugby players!

The edition I read was ISBN: 0-14-043-135-7.

Citation:

Hardy, Thomas. Tess of the d'Urbervilles. Markham: Penguin Books, 1983. Print.

Lodge, David. The Art of Fiction. Toronto: Penguin Books, 1992. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment